Li Po (李白), also known as Li Bai, is generally believed to have been born in 701, in Suyab (present-day Kyrgyzstan) where his family had prospered in business at the frontier. According to legend, while Li Po’s mother was pregnant with him, she had a dream of a great white star falling from heaven. This seems to have contributed to the idea of his being a banished immortal (one of his nicknames). Later, the family, after a decision by his father, Li Ke (李客), moved to Jiangyou (江油), near modern Chengdu, in Sichuan, when the young boy was about five years old. During his lifetime, he had many names—Li Taibai, Green Lotus Scholar, Li Twelve, the last one a familial term of endearment, due to his being twelfth among his brothers and male cousins on the paternal side. As a young man he read widely in Confucian classics and astrological and metaphysical tomes but disdained to take the literacy exam. Reading extensively was part of the family literary tradition. Before he was ten he had begun to compose poetry.

Li Po (李白), also known as Li Bai, is generally believed to have been born in 701, in Suyab (present-day Kyrgyzstan) where his family had prospered in business at the frontier. According to legend, while Li Po’s mother was pregnant with him, she had a dream of a great white star falling from heaven. This seems to have contributed to the idea of his being a banished immortal (one of his nicknames). Later, the family, after a decision by his father, Li Ke (李客), moved to Jiangyou (江油), near modern Chengdu, in Sichuan, when the young boy was about five years old. During his lifetime, he had many names—Li Taibai, Green Lotus Scholar, Li Twelve, the last one a familial term of endearment, due to his being twelfth among his brothers and male cousins on the paternal side. As a young man he read widely in Confucian classics and astrological and metaphysical tomes but disdained to take the literacy exam. Reading extensively was part of the family literary tradition. Before he was ten he had begun to compose poetry.

The young Li also engaged in other activities, such as taming wild birds, fencing, riding, hunting, traveling and aiding the poor or oppressed by means of both money and arms. Eventually, the young Li seems to have become quite skilled in swordsmanship: When I was fifteen, I was fond of sword play, and with that art I challenged quite a few great men. Before he was twenty, Li had fought and killed several opponents, apparently for reasons of chivalry, in accordance with the knight-errant tradition of dueling. In 720, he was interviewed by Governor Su Ting, who considered him a genius. Though he expressed the wish to become an official, he never took the civil service examination that would have made him a ranking officer. Instead, when he was eighteen or nineteen, he went into seclusion with a Daoist recluse, studied the Daoist religion, and, at twenty-three, began touring China.

In his mid-twenties, about 725, Li left Sichuan beginning his days of wandering. Soon after that he married the granddaughter of a retired prime minister, Xü Yushi, and lived with his wife’s family in Anlu (present-day Hubei province). As he wrote to a friend, The land of Chu has seven swamps. I went to look at them. But at His Excellency Xü’s house, I was offered the hand of his granddaughter and lingered there during the frosts of three autumns. He had already begun to write poems, some of which he showed to various officials in the vain hope of becoming employed as a secretary. He seems to have abandoned Miss Xü, who was impatient at his lack of promotion. During the first year of his wandering, he met celebrities and gave away much of his wealth to needy friends. He is known to have married four times. After that first marriage ended, he married, in 744, for the second time, another poet, surnamed Zong (宗), with whom he both had children and exchanges of poems, including many expressions of love for her and their children. His wife was a granddaughter of Zong Chuke an important government official during the Tang dynasty. He also married a Miss Lin and a Miss Lu. He was, also, reputably fond of going about with the dancing-girls of Zhaoyang and Jinling.

By perhaps 740, he moved to Rencheng city in Shandong province. It was at that time that he became one of the group members known as the “Six Idlers of the Bamboo Brook,” an informal group of like-minded individuals dedicated to literature and wine, and reputedly constantly drunk. He continued his wandering, eventually making friends with a famous Daoist priest, Wu Yun. In 742, Wu Yun was summoned by the Emperor to attend the imperial court, where his praise of Li led Emperor Xuan-zong to summon Li Po to the court in Chang’an and offer him a position at the Imperial Academy where he was employed as a translator, as he knew at least one non-Chinese language. The emperor gave him a post at the Hanlin Academy that served to provide scholarly expertise and poetry for the imperial court. He continued to enjoy drinking to excess. One day, the emperor had a sudden impulse and wanted Li Po to write a song expressive of his blue mood. When Li Po obeyed the summons, he was so drunk that courtiers were obliged to dab his face with water. When in a short while he came to his senses a little bit, he seized a brush and, without any visible efforts, wrote a composition of flawless gracefulness. However, he was not universally popular and came under attack from envious noblemen in the court and so the emperor, reluctantly, but politely, and with large gifts of gold and silver, sent Li Po away from the royal court to resume his simple previous life.

The influence of alcohol in his poetry is explored in a brief article in The Guardian by Ben Myers : Here is a poet whose “technique” involved climbing a mountain, getting wasted, then writing down his thoughts. The work he produced during such jollies was highly meditative, though only in the same way the drunk in the corner of your local pub is meditative, while his ability to convey the skull-crushing, fear-inducing effect of hangovers is second to none… Much of his work is imbued with that sense of warmth and oneness that comes after the first few glasses, as well as that maudlin regret that comes with the next few.

After leaving the court, Li Po formally became a Taoist, making a home in Shandong, but wandering extensively for the next ten years, writing poems. At about this time, around the autumn of 744, he met Du Fu, with whom he shared social concerns, and the two poets became good friends. They shared a single room and conducted various activities together, such as traveling, hunting, wine, and poetry. In 756, Li Po became unofficial poet laureate and staff adviser to the military expedition of Prince Lin of Yong, Emperor Ming-Huang’s 16th son who was named to share the imperial power as a general after the old emperor had abdicated. The prince was soon accused of intending to establish an independent kingdom and was executed. Li Po escaped, but was later captured, imprisoned and sentenced to death. In the summer of 758 he was banished to Yelang; before he arrived there, he benefited from a general amnesty. He had only gotten as far as Wushan when the good news of his pardon caught up with him in 759.

When Li received the news of his pardon, he returned down the river to continue his wandering lifestyle while still engaging in the pleasures of food, wine, good company, and writing poetry. Eventually, in 762, Li’s relative Li Yangbing became magistrate of Dangtu, and Li Po went to stay with him there. He volunteered to serve on the general staff of the Chinese commander Li Guangbi. However, at age 61, Li Po became critically ill and his health would not allow him to fulfill this plan. There is a long and fanciful tradition regarding his death that he drowned after falling from his boat one day while drunk, as he tried to embrace the reflection of the moon in the Yangtze River. However, the truth appears to be that he died in a relative’s house, having contracted his last illness as the result of falling into the water while drunk. The actual cause appears to have been natural enough, although perhaps exacerbated by his hard-living lifestyle. Some claimed that his death was the result of mercury poisoning due to alcohol consumption. Others claimed that he died of chronic thoracic suppuration—pus penetrating his chest and lungs. These include the poet Pi Rixiu (838–83) in his poem Seven Loves: He was brought down by rotted ribs, / Which sent his drunken soul to the other world. Although there is no way to verify this claim, it has credibility – such a chest problem could have been caused by abuse of alcohol. In his final years, Li Po’s drinking and poverty would have aggravated his pulmonary condition. Nevertheless, whatever the truth, the legend surrounding his death has a place in Chinese culture and continues to be propagated to this day

In January 764, the newly enthroned emperor Daizong issued a decree summoning Li Bai to serve as a counselor at court. It was a post without actual power, in spite of its high-sounding title. When the news reached Dangtu County, where Li Po was supposed to be living, local officials were thrown into confusion and could not find him. Soon it was discovered that he had died more than a year before. Of what cause and on what day, no one could tell. So we can say only that Li Po, despite his renown, passed away in 762 without notice. For hundreds of years, some people even maintained that he had never died at all, claiming to encounter him now and then. In truth, the exact date and cause of his death remains clouded in uncertainty.

In 1962, to commemorate the 1200th anniversary of the death of famous Chinese poet, Li Po (also known as Li Bai) the Li Bai Memorial Hall (right) was built at his birthplace, Zhongba Town of northern Jiangyou County in Sichuan Province. It was completed in 1981 and opened to the public in October 1982. The memorial, built in the style of the classic garden of the Tang Dynasty, has collected Li Po’s works in 80 different editions printed in the Yuan (1271-1368), Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, 700 volumes in total. Li Po lived in Jiangyou for 24 years during the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907).

Quiet Night Thought

Quiet Night Thought is one of the most famous Chinese poems taught regularly in Chinese and Taiwanese schools. This brief poem has a similar iconic status in Chinese literature as Sappho’s fragment on the moon and the Pleiades has in Greek literature or Basho’s frog haiku in Japanese literature. The brief poem was written by Li Po on September 15th in the 14th year of Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty (726) in Yangzhou Hostel, when he was 26 years old. Reputedly the hostel was not in good condition: it had poor ventilation, the rooms were cold and, it has been suggested, the water sprinkled on the ground condensed quickly into frost. According to some scholars, the poem was written at the time of the Mid-Autumn Festival in which family reunions are very important. That could have added to the sense of homesickness in the poem.

In traditional Chinese, the poem reads:

床前明月光

疑是地上霜

舉頭望明月

低頭思故鄉

In simplified Chinese, it reads:

床前明月光

疑是地上霜

举头望明月

低头思故乡

And in Pinyin Chinese, it reads:

Chuáng qián míngyuè guāng

Yí shì dìshang shuāng

Jǔtóu wàng míngyuè

Dītóu sī gùxiāng

A literal translation might read

Moonlight before my bed

Perhaps frost on the ground.

Lift my head and see the moon

Lower my head and I miss my home.

An even more literal translation, courtesy of Ravi Kopra, reads

Bed before bright moon shine

Think be ground on frost

Raise head view bright moon

Lower head think home

The poem is structured as a single quatrain (4 lines) in five-character regulated verse in a form called Shi (诗), which although it merely means “poetry” in Chinese, in English it means, more specifically, poetry modeled after works in the Old Chinese, Confucian style. Shi poems are generally quatrains, as in Quiet Night Thought, with a line length of four to seven characters and, usually, a rhyme scheme ABAB. In this case the poem is structured as a single quatrain in five-character regulated verse with a simple AABA rhyme scheme. It is short and direct, as Shi poems are, and is not merely personal but also evocative of all those who are away from home through their obligations. Quiet Night Thought is considered unusual among Li Po’s poems for its vagueness and its lack of personal details.

According to Delaine Rogers, in her essay Spring Dawns and Quiet Night Thoughts, this brief poem embodies the concept of

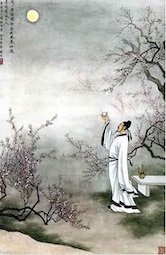

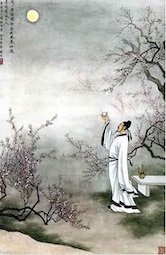

filial piety: Li Bai, as the narrator, fulfills his duty toward the Emperor by serving his government post, and fulfills his duties toward his ancestors by thinking of and missing his hometown, lamenting the fact that he cannot reunite with his family for the Mid-Autumn Festival. This festival, Zhong Qiu Jie, which takes place on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month, is celebrated by eating the popular, traditional mooncakes and is associated with family reunions. Others have discounted the connection with the Mid-Autumn Festival. The association with drinking is harder to discount. Many paintings of Li Po, such as that on the right, depict him in a flowing white robe and beard, raising a glass of wine to the moon.

Quiet Night Thought is unusual among Li Po’s poems for its vagueness. The details of the moon and of his surroundings, with the lack of personal details, makes this poem easily relatable. The moon referred to here is most likely the mid-autumn moon, given the time of year. The poem also embodies the concept of filial piety: Li Po, as narrator, fulfills his duty toward the Emperor by serving his government post, and fulfills his duties toward his ancestors by thinking of and missing his hometown, lamenting the fact that he cannot reunite with his family.

Li Po, as explained in the biographical note above, was also a regular drinker. He celebrated drunkenness and the potency of wine, and wrote many of his poems while inebriated. It has been suggested that he wrote Quiet Night Thought drunk. Author Jingxiong Wu states while some may have drunk more wine than Li, no-one has written more poems about wine.

Sri Lankin writer Isuru Thambawita offers a detailed analysis of the poem. Going through the first line of this poem, what springs to our minds is the fact that the poet can directly cast a glance at the moon. Firstly, he sees the moon which has brought and refreshed the memories of his beloved ones and the village. Secondly, comes a comparison between the frost and the moonbeams. The poet through his imagination has captured the night scenery in a mesmerising manner. The dew on the gossamer scattered throughout the garden has been compared by the poet to moonbeams. On the other hand, it can be said that Li Bai has been fascinated by this morning view. Next comes the third line which portrays that the poet’s memory and feelings get triggered by the moon. Obviously the moon, as you are aware, has been used by the poets to portray nuances of feelings and ideas such as love, loneliness, hatred, sorrow, misery and happiness. Going back to the fourth line of the poem, it is clear that he closes his eyes hiding nostalgic feelings in his heart.

Translating the poem

Like many, I first encountered the poetry of Li Po when I read Ezra Pound‘s celebrated poem, The River-Merchant’s Wife: A Letter which is subtitled after Li Po. It is his translation or reinterpretation of a classic Li Po poem which Pound first published in his 1915 collection Cathay which contains versions of Chinese poems composed from the notebooks of Ernest Fenollosa, a scholar of Chinese literature. It is one of eleven poems in the collection based on poems by Li Po, called Rihaku in Cathay. Although Pound was largely responsible for the eminence of Li Po’s work in contemporary literature and although he translated or adapted widely from the Chinese, there is no evidence that he translated Quiet Night Thought.

Arthur Waley, the renowned English orientalist and sinologist who achieved much acclaim for his translations of Chinese poetry, also translated many of Li Po’s poems, particularly in his collection A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems (1918). But again, there is no evidence that he translated Quiet Night Thought.

Amy Lowell, who had a distinctly frosty relationship with Pound through their fractious collaboration in the Imagist (or Imagiste) movement was one of the first Western writers to translate Li Po’s poem. (See below.) Whether it does justice to the original, I am unqualified to say but it stands as an interesting brief poem on its own merits. Since her translation, there have been numerous others who have added to the store of translations of this iconic poem. Of the versions included, I enjoy that of Zhao Zhentao for its compression, that of Vikram Seth for its balance and that of Aaron Poochigian for its alliteration, its rhymes and its colloquial zest. Inspired by the rhythms and rhymes of Robert Frost’s Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening, I offer my own tribute to Li Po’s poem as the last translation below.

Should you wish to translate the poem or to select a favourite translation, you might fill in the comment box below this post.

English Translations

床前明月光

疑是地上霜

舉頭望明月

低頭思故

***

Thoughts in a tranquil night

Athwart the bed

I watch the moonbeams cast a trail

So bright, so cold, so frail.

That for a space it gleams

Like hoar-frost on the margin of my dreams.

I raise my head, —

The splendid moon I see:

Then droop my head,

And sink to dreams of thee —

My Fatherland, of thee!

Launcelot Alfred Cranmer-Byng

***

Night Thoughts

In front of my bed the moonlight is very bright,

I wonder if that can be frost on the floor?

I lift up my head and look at the full moon, the dazzling moon.

I drop my head, and think of the home of old days.

Amy Lowell

***

Quiet Night Thoughts

Before my bed there is bright moonlight

So that it seems like frost on the ground;

Lifting my head I watch the bright moon,

Lowering my head I dream that I’m home.

Arthur Cooper

***

Thoughts in Night Quiet

Seeing moonlight here on my bed

and thinking it’s frost on the ground,

I look up, gaze at the mountain moon,

then back, dreaming of my old home.

David Hinton

***

Thoughts On a Quiet Night

Moon-glitter

at the foot of my bedroll

seems on waking

to be feathers of frost.

I raise my head to gaze

at the glittering moon itself

then sink back

longing for home.

Stanton Hager

***

Thoughts in the Silent Night

Beside my bed a pool of light—

Is it hoarfrost on the ground?

I lift my eyes and see the moon,

I lower my face and think of home.

Yang Xianyi and Dai Naidie

***

Still Night Thoughts

Moonlight in front of my bed —

I took it for frost on the ground!

I lift my eyes to watch the mountain moon,

lower them and dream of home.

Burton Watson

***

In the Quiet Night

The floor before my bed is bright:

Moonlight — like hoarfrost — in my room.

I lift my head and watch the moon.

I drop my head and think of home.

Vikram Seth

***

On a Quiet Night

I saw the moonlight before my couch,

And wondered if it were not the frost on the ground.

I raised my head and looked out on the mountain moon;

I bowed my head and thought of my far-off home.

Shigeyoshi Obata

***

Quiet night thoughts

The moon light

Shining in front of my bed

More like the frost on the grass

On raising my head

I can glance at the moonlight

On lowering my head

I remember my home village

Nostalgic feelings

Isuru Thambawita

***

A Quiet Night Thought

Moonlight before my bed

Perhaps frost on the ground.

Lift my head and see the moon

Lower my head and pine for home.

Quiet Night Thought

I see bright moonlight

on the floor by my bed

It looks like fresh

frost on the ground

I lift my head

and see the moon

I lower my head

missing my home

How I wish I

am there soon!

Ravi Kopra

***

Thoughts on a Still Night

My bed is flooded with moon light tonight

I wonder if the frost has crept in

I raise my head and see the shining moon

I lie back in bed missing my hometown.

Ravi Kopra

***

Silent Night Thoughts

Bright moon shines beside the bed

Like frost on soil

I raise my head and watch the moon

I lower my head and think of home.

Max Gladstone

***

In the Quiet Night

So bright a gleam on the foot of my bed —

Could there have been a frost already?

Lifting myself to look, I found that it was moonlight.

Sinking back again, I thought suddenly of home.

Witter Bynner

***

Night Thoughts

Before my bed, the moon shines bright;

Be it frost aground? I suppose it might.

I lift my head, the moon to behold, then

Lower it, musing: I’m homesick tonight.

Andrew W.F. Wong

***

A Quiet Night Thoughts

The moonbeam lies in front of my seat;

I doubt it can thaw the frosted ground before the dawn.

Holding up, I look into the cool moon hung over my head;

With head bowed, I deep in thoughts of my remote kinsmen.

Alexander Goldstein

***

Quiet Night Thoughts

A pool of moonlight on my bed in this late hour

like a blanket of frost on the world.

I lift my eyes to a bright mountain moon.

Remembering my home, I bow.

Sam Hamill

***

Quiet Night Thought

Mid-Autumn Festival Poem

Moonlight in front of the bed,

Perhaps frost on the ground.

I look up at the bright moon

I look down and think of my hometown.

Lisa Yannucci

***

Quiet Night Thought

There, past the footboard, gleaming in the gloom,

is moonlight, right? Or frost that’s formed too soon.

I lift my head and recognize the moon.

I settle back and reminisce of home.

Aaron Poochigian

***

Thoughts on a Quiet Night

Before my bed the bright moon shines its light,

Perhaps the frost now covers all the ground;

I lift my head to see the shining moon,

I bow my head to see my native town.

Frank Watson

***

Night Thoughts

The moonlight falls by my bed.

I wonder if there’s frost on the ground.

I raise my head to look at the moon,

then ease down, thinking of home.

Arthur Sze

***

Quiet Night Think

Before my bed, the moon is shining bright,

I think that it is frost upon the ground.

I raise my head and look at the bright moon,

I lower my head and think of home.

Gillian Sze

In the Still of the Night

By the bed a puddle of bright moon-glow

like left over morning snow

My head raised, basking in the bright moon

Head bowed, thinking of the old hometown only I still know

Art Lu

***

Thoughts of a Quiet Night

Before the bed, bright moonlight.

I took it for frost on the ground.

I raised my head to dream upon that moon,

then bowed my head, lost, in thoughts of home.

J. P. Seaton

Quiet Night Thoughts

I wake and my bed is gleaming with moonlight

Frozen into the dazzling whiteness I look up

To the moon herself

And lie thinking of home

W. S. Merwin

***

Reflection in a Quiet Night

Moonlight spreads before my bed.

I wonder if it’s hoarfrost on the ground.

I raise my head to watch the moon

And lowering it, I think of home.

Ha Jin

***

Night Thoughts

Bright shines the Moon before my bed;

Methinks ’tis frost upon the earth.

I watch the Moon, then bend my head

And miss the hamlet of my birth.

Jarek Zawadski

***

Thoughts on a Quiet Night

Before my bed the light is so bright

it looks like a layer of frost

lifting my head I gaze at the moon

lying back down I think of home

Red Pine

***

Thoughts in the Silent Night

Moonlight shining through the window

Makes me wonder if there is frost on the ground

Looking up to see the moon

Looking down I miss my home town

Fercility Jiang

***

Thoughts in the silent night

Moonlight before my bed,

Could it be frost instead?

Head up, I watch the moon;

Head down, I think of home.

Zhao Zhentao

***

Quiet Night / after Li Po

Moonlight spills

across the bed,

outside the frost

is deepening.

I lie awake and

watch the changing

shadows, thinking

of the lonely earth.

John Haines

***

Night Thoughts

Moon

Before the bed,

Or

Frost on the ground?

Lifting my head

I see the moon,

Looking down,

I remember home.

Wong May

***

Thoughts on a Still Night

The pale glow by my bed

I mistook for a frost

was the bright moon reminding me

of home comforts lost

Donal Clancy

***

Quiet Night Thoughts

Moonlight illuminates my bed

as frost brightens the ground.

Lifting my head, the moon allures.

Lowering my eyes, I long for home.

Michael R. Burch

***

A Quiet Night Thought

I watch from bed the moon’s light glow

And frost upon the floor like snow;

I raise my head, I see the moon.

I dream of home left years ago.

Conor Kelly

LINKS

The Wikipedia page on Li Bia

The Wikipedia page on Quiet Night Thought

The Tang-period Poet Li Bai’s Legacy

Articles on Li Po on the First Known When Lost site

The poet and the poem are discussed by Delaine Rogers on the Spring Dawns and Quiet Night Thoughts post

Andrew W.F. Wong discusses the poem and his various efforts to translate it

Max Gladstone on translating the poem

On controversies surrounding the poem

The plastered poetic genius of Li Po by Ben Myers

An essay on the poem by Isuru Thambawita

Li Po (李白), also known as Li Bai, is generally believed to have been born in 701, in Suyab (present-day Kyrgyzstan) where his family had prospered in business at the frontier. According to legend, while Li Po’s mother was pregnant with him, she had a dream of a great white star falling from heaven. This seems to have contributed to the idea of his being a banished immortal (one of his nicknames). Later, the family, after a decision by his father, Li Ke (李客), moved to Jiangyou (江油), near modern Chengdu, in Sichuan, when the young boy was about five years old. During his lifetime, he had many names—Li Taibai, Green Lotus Scholar, Li Twelve, the last one a familial term of endearment, due to his being twelfth among his brothers and male cousins on the paternal side. As a young man he read widely in Confucian classics and astrological and metaphysical tomes but disdained to take the literacy exam. Reading extensively was part of the family literary tradition. Before he was ten he had begun to compose poetry.

Li Po (李白), also known as Li Bai, is generally believed to have been born in 701, in Suyab (present-day Kyrgyzstan) where his family had prospered in business at the frontier. According to legend, while Li Po’s mother was pregnant with him, she had a dream of a great white star falling from heaven. This seems to have contributed to the idea of his being a banished immortal (one of his nicknames). Later, the family, after a decision by his father, Li Ke (李客), moved to Jiangyou (江油), near modern Chengdu, in Sichuan, when the young boy was about five years old. During his lifetime, he had many names—Li Taibai, Green Lotus Scholar, Li Twelve, the last one a familial term of endearment, due to his being twelfth among his brothers and male cousins on the paternal side. As a young man he read widely in Confucian classics and astrological and metaphysical tomes but disdained to take the literacy exam. Reading extensively was part of the family literary tradition. Before he was ten he had begun to compose poetry.

Jane Hirshfield

Jane Hirshfield